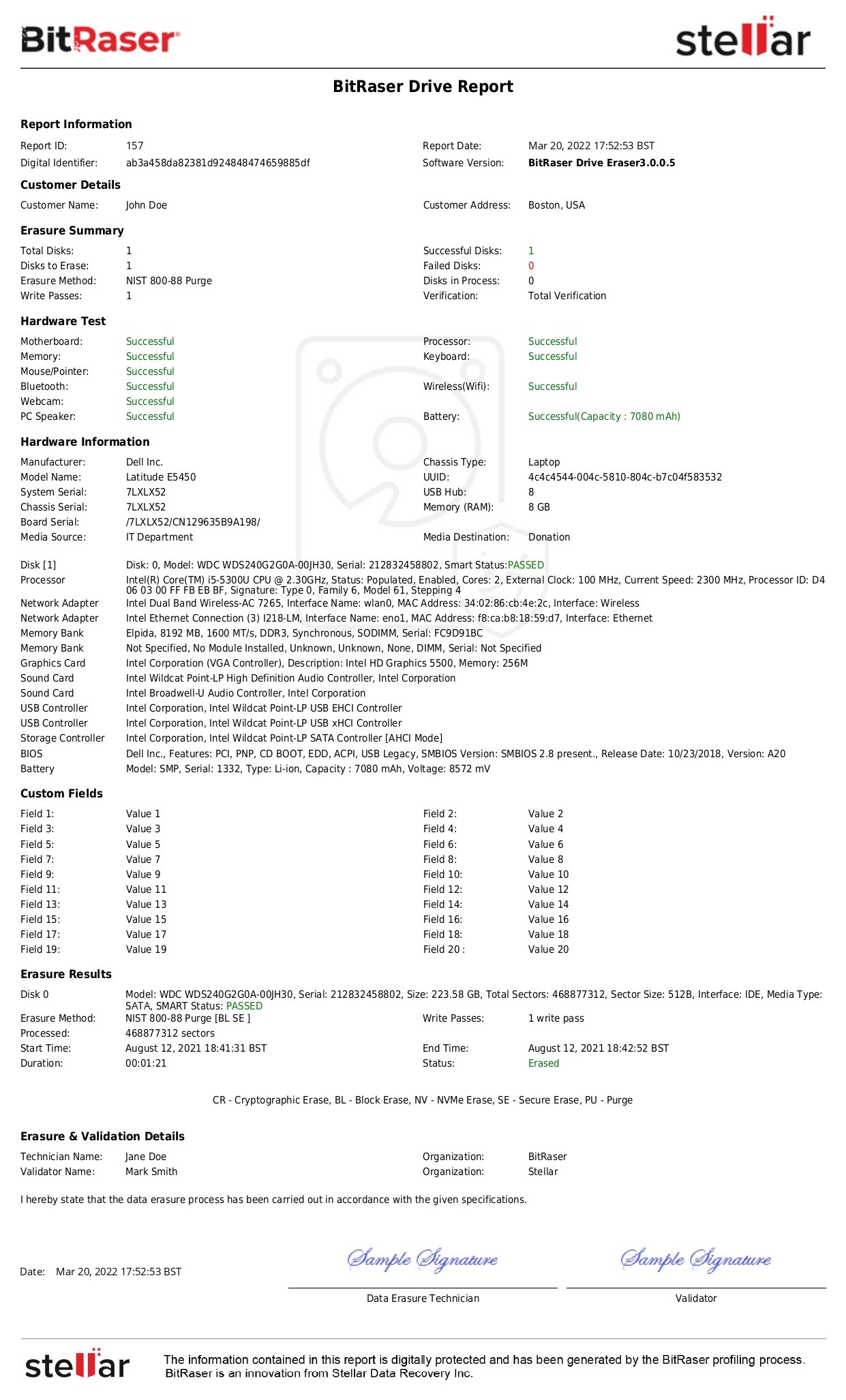

A March 3, 2020 press release by the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) mentions that Dr. Steven A. Porter's medical practice will have to pay US$100,000 to the Office for Civil Rights (OCR) for HIPAA compliance failure. Dr. Porter, a gastroenterologist based in Utah, also has to take corrective actions to ensure no further HIPAA violation. His practice will remain under monitoring for two years to check his compliance with the corrective action plan. The OCR investigation started after a breach complaint lodged by a business associate of Dr. Porter. The OCR determined that Dr. Porter had not conducted a proper and rigorous risk assessment when the breach got reported. Considerable technical assistance was available to Dr. Porter during the investigation. However, he failed to take advantage of that to execute a thorough risk assessment and incorporate corrective measures during the investigation.

HIPAA Compliance Is Not A Choice, It Is The Law

It is imperative that you ensure HIPAA compliance if you have anything to do with healthcare in the U.S. Whether yours is an individual service or a healthcare service delivery organization, you are within the purview of HIPAA. Yours may be a company that has little to do with healthcare apart from offering healthcare plans to employees. Even then, you need to know about HIPAA compliance and implement the necessary measures. The same applies to health insurance agencies. This article will help you fully understand the actions you need to execute for HIPAA compliance with reference to the HIPAA Privacy Rule. It makes poor business sense to end up paying a hefty fine for failing to grasp what a law implies in practical terms.

What Is HIPAA?

The origin of HIPAA lies in the 1996 law that allows workers to carry forward their insurance and healthcare rights when they change jobs. HIPAA has since evolved to be a far more comprehensive law.

After the latest amendments in 2013, HIPAA has become a law that impacts the entire healthcare industry in the US. It applies to both individuals and organizations and on both sides: those who deliver it and those who receive it. HIPAA, thus, has implications for healthcare delivery agencies, individual healthcare professionals, and patients. It also applies to other related agencies such as insurance companies and firms that offer healthcare plans to their employees.

What HIPAA Aims To Achieve

According to the online HIPAA Journal, the main objectives of HIPAA are to:

- Make healthcare delivery in the US more efficient

- Eradicate wastage in the US healthcare system

- Counter healthcare insurance frauds

- Govern tax provisions for medical savings accounts

- Ensure that individual health data remain private, protected, and confidential

- Allow workers with pre-existing medical conditions to remain eligible for occupational health insurance schemes

The Two Main Action Points For The Government

The two key actionable points for the US government with reference to HIPAA relate to the privacy and security of health information. This law makes the Secretary, of HHS, responsible for developing standardized regulations to protect the privacy and security of specific health information.

The Secretary, HHS, has accordingly issued nationalized standards. These are contained in the documents popularly known as the HIPAA Privacy Rule and the HIPAA Security Rule. This article gives a simplified but thorough exposure to what the HIPAA Privacy Rule is all about, with action points clearly enlisted.

HIPAA Privacy Rule

The formal name for the national standards relating to the privacy of health information under HIPAA is, "Standards for Privacy of Individually Identifiable Health Information." These are the first standards ever formulated at the national level for protecting the specified health data of individuals.

These standards define the extent to which organizations can use and disclose the "protected health data" of individuals. They draw from the individual right to privacy enshrined in the U.S. Constitution. The standards also assist individuals to understand and control their health information. On the one hand, the free flow of health-related information is necessary for quality healthcare delivery. On the other hand, individuals have a right to privacy. The standards aim to maintain a balance between these two.

What Information Is Protected Under HIPAA?

The Privacy Rule of HIPAA marks all "individually identifiable health information" as "protected health information" (PHI). PHI includes, but is not limited to, the following:

- All demographic data

- Common identifiers like name, address, social security number, etc.

- All past, present, and future information related to the physical and mental health condition of an individual

- Healthcare provision available to an individual

- Past, present, and future payment for the healthcare provisions available to an individual

The employment record preserved by an employee is beyond the scope of PHI. So is educational data as permitted by the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act, 20 U.S.C. §1232g.

No restrictions apply to de-identified health data. Health information that does not in any way identifies an individual, nor supplies any reasonable basis for identification, qualifies as de-identified.

There are two ways of de-identifying health information. A qualified statistician may determine whether health information is de-identified or not. The other means is to remove particular identifiers of individuals, members of their households, and employers.

To Whom The HIPAA Privacy Rule Applies

HIPAA refers to items, individuals, and organizations within the scope of the Privacy Rule as "covered entities." We provide a list of covered entities below:

Health Plans: Individual or group health plans that provide healthcare or pay for it are within the scope of the HIPAA Privacy Rule. Health plans include:

- Health insurers, including dental and vision health

- Insurers of prescription drugs

- Health Maintenance Organizations (HMOs)

- Medicare

- Medicaid

- Medicare + Choice

- Insurers of Medicare supplements

- Sponsored group health plans - by employers, the government, or the church

Exceptions to the above:

- A group health plan with less than 50 participants established and maintained only by the employer is not a covered entity.

- A program like the food stamps program funded by the government is not a covered entity as it does not have healthcare payment or provision as its main purpose.

- Programs like a community health center that intends to provide healthcare directly, not organize payment for healthcare, is not a covered entity.

- Government grants meant to fund providing healthcare are not covered entities.

- Insurances that provide workers; compensation, and automobile, casualty, or property insurance are not covered entities.

- If an insurance plan has separate lines of business one of which is healthcare, only the part that relates to healthcare is a covered entity.

Healthcare Providers: Any healthcare provider transmitting information electronically about particular transactions is a covered entity. The size of the healthcare-providing institution or individual practice does not matter.

Healthcare providers include organizations like hospitals, and individuals like physicians, and other healthcare practitioners. Whether the healthcare provider executes the transactions directly or through a billing service does not make a difference. The HIPAA Transactions Rule enlists the types of transactions to which the privacy rule applies. Standard transactions include:

- Advice regarding payments and remittance

- Status of claims

- Coordination of benefits

- Eligibility information

- Information about claims and encounter

- Enrollment and de-enrollment information

- Information related to the payment of premiums

Covered entities under HIPAA who transmit any of the above transactions electronically must use an ASC X12N standard form or the NCPDP for specified pharmacy transactions.

Healthcare Clearinghouses: These are agencies that receive non-standardized data from another entity and transform them into the relevant standardized format. The reverse is also true. Clearinghouse functions typically include billing services, community health management information services, and repricing functions. Healthcare clearinghouses become covered entities if they handle PHI.

Business Associates: A business associate is an individual or an organization that is not on the salary roll of a covered entity, but performs certain functions for a covered entity. An agency helping a healthcare provider to gain accreditation, for example. A business associate becomes a covered entity only if the services they provide expose them to any PHI item. In such a situation, the covered entity needs to include non-disclosure clauses in its contract with the business associate.

Uses and Disclosure: General Principle

The basic principle guiding the HIPAA Privacy Rule is to enable an individual to have control over the use and disclosure of PHI by a covered entity. A covered entity may disclose or use information not covered under PHI.

A covered entity may disclose or use any PHI item only if the concerned individual has expressed consent in writing. However, the HIPAA Privacy Rule defines two situations where a covered entity requires to disclose PHI.

When You Must Disclose PHI?

If an individual or their authorized representative asks for access to any PHI item, a covered entity requires to facilitate such access. A covered entity also requires to disclose PHI when the HHS needs such access to investigate compliance or review enforcement. When law enforcement or judicial inquiry needs PHI disclosure, a covered entity has to abide by that. A covered entity also has to disclose PHI to facilitate legal proceedings for victims of abuse and trauma. You may have a reasonable doubt in certain situations that non-disclosure of PHI may lead to some serious harm to any individual, the patient included, or to the public. You are obligated to disclose it to the relevant authority.

When You May Disclose and/or Use PHI?

The HIPAA Privacy Rule also lays down situations where a covered entity may disclose and use PHI. Such situations do not obligate a covered entity to disclose, as in the case of the above two required situations.

A covered entity has permission to reveal PHI to the individual whose PHI it is. A covered entity also has permission to disclose and use PHI for treatment, payment, and healthcare operations.

When more than one healthcare providers need to consult for effective treatment of an individual, a covered entity may disclose and use PHI. The same applies when a covered entity needs to refer a patient to another covered entity. A covered entity has permission to disclose and use PHI for claiming reimbursement for treatment carried out under a health plan. The same applies when PHI use is necessary for premium payment, or to determine the full scope of insurance coverage and its benefits.

Healthcare operations in this context refer to the following:

- Case management and care coordination for improved healthcare delivery and/or quality assessment.

- Competency assessment for accreditation, credentialing, & evaluation of health plan or provider.

- Organizing and/or conducting medical reviews or audits, and legal services under compliance programs, fraud investigation, and abuse detection.

- Insurance activities like underwriting, risk rating, and assessing reinsurance risk.

- Planning, administration, management, and development of business.

- Using de-identified PHI for fundraising for a covered entity.

Individual's Right To Agree Or Object

PHI disclosure and use need written consent from the patient unless it is a medical emergency where the patient lacks the capacity to give consent. An individual has the full right to object to the disclosure and use of PHI.

Exceptions to obtaining written consent are as follows:

- A covered entity such as a healthcare delivery organization may assume informal consent in maintaining a directory of patient contact information.

- A covered entity may disclose the condition of the patient and their location to anyone asking for the patient by name.

- The religious affiliation of patients may be disclosed to the clergy without naming them.

- A covered entity may rely on a patient's informal consent for notifying family members of patients, getting help from them such as buying medicine, and for treatment planning and payment needs.

- Written consent is not necessary for disclosing PHI for public health needs in the 12 priority areas of national health.

- There is permission for the use of PHI without the individual's written consent for public benefit and research, though identifiable information must be limited to the minimum.

- Written consent is not necessary if PHI disclosure is necessary for the protection of victims of domestic violence, abuse, or neglect.

- Incidental disclosure is not considered a violation if that happens after a covered entity has conducted a proper risk assessment and put in place all necessary privacy requirements.

Action Points For Covered Entities To Ensure HIPAA Privacy Rule Compliance

- Develop a privacy policy, complete with the procedures for implementing the policy. Include a complaints option by users and steps for mitigation.

- Designate a person among your staff as responsible for developing, implementing, and monitoring all practices that relate to your privacy policy and procedures.

- Organize staff training to ensure that everyone fully understands the privacy requirements.

- All users must receive notice of a covered entity's privacy practice.

- Such notice distribution must be completed within the first five direct encounters in the case of in-person treatment interactions.

- In the case of electronic healthcare delivery, the distribution must happen immediately through electronic response.

- By prompt mailing in the case of telephonic service delivery.

- All covered entities must also display the notice at a prominent place where people visiting the service can easily see it.

- A covered entity should request users to give an acknowledgment receipt of getting the privacy practice notification.

- Ensure that users have easy access to their own PHI and other health records as and when they need those or ask for them.

- Ensure compliance with disclosure accounting. A user has the right to ask for the accounts of their PHI disclosure for up to a period of six years from the date when the PHI collected the PHI.

- Ensure that you comply with reasonable requests from users for confidential communications. For instance, a user has the right to request health-related communications to be delivered to an address separate from their residential address.

- Conduct a risk assessment and make reasonable arrangements for PHI data privacy.

- Do not try to retaliate if a user complains to the HHS and has an investigation conducted, even if the investigating authority decides that you were not at fault.

- Do not ask any user for a waiver of any right under the privacy rule.

- Retain all data relevant to privacy compliance for a period of six years.

Two Special Cases

A personal representative such as a legal representative authorized by an individual is equal to the authorizing individual. A covered entity has to allow the representative all rights granted to an individual user under the HIPAA Privacy Law.

For minors, all rights granted to an individual user transfer to the minor's parents, or the legal guardian in case the parents are not alive or functional.

Penalty For Non-Compliance

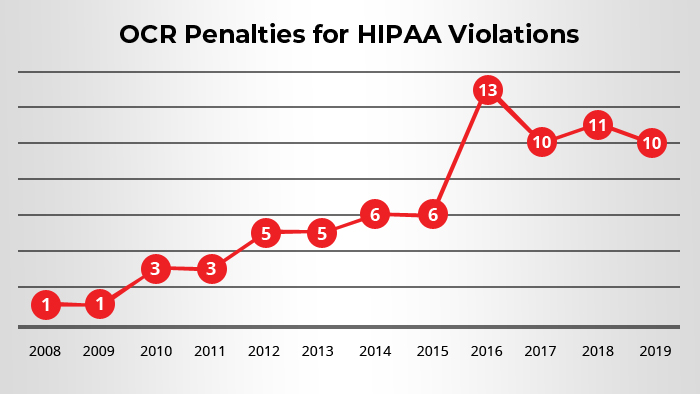

The Office for Civil Rights (OCR), HHS, is responsible for enforcing HIPAA Privacy Rule compliance. The OCR is also responsible to review compliance and address complaints of non-compliance through conducting investigations.

All covered entities should have implemented all the standards required by the Privacy Rule no later than April 14, 2003. Only small health plans had an extension up to April 14, 2004, for compliance.

Civil Monetary Penalties

Hopefully, therefore, if you are a covered entity reading this piece, you have everything in place already. In case you've identified any gap, address that immediately. Non-compliance may attract monetary fines.

The OCR has the right to levy civil money penalties as detailed below:

- Up to US$100 per violation for those that had occurred before February 18, 2009. However, the total penalty cannot exceed US$ 25,000 for a calendar year.

- For violations occurring after February 18, 2009, the penalty per violation can go up to US$50,000 or more. The calendar year cap is a whopping US$1,500,000.

In case the violation was not because of willful negligence and got addressed within 30 days or less of receiving the complaint, there will be no penalty. The OCR has sole discretion in determining whether the violation was due to willful negligence. The OCR must submit a notice to the covered entity about its intention to levy a monetary penalty. The covered entity has the right to submit written evidence that may lessen or cancel the penalty within 30 days of receiving the notice. A covered party may also request an administrative hearing.

Criminal Penalties

If the Privacy Rule violation happens not because of willful neglect, but due to deliberate action, it will attract criminal penalties. The U.S. Department of Justice is responsible to conduct all criminal proceedings for Privacy Rule violations.

The penalty details are enlisted below:

- Up to one year of imprisonment and criminal penalty of up to US$50,000

- Up to five years in prison and a criminal penalty of up to US$100,000 if the deliberate action of securing and divulging PHI involves the use of false pretenses

- Up to 10 years imprisonment and a criminal penalty of up to US$250,000 if the deliberate act of collecting and disclosing PHI is for any commercial gain, personal advantage, or malicious intent.

Doublecheck Or Celebrate

If you are a covered entity reading this piece, double-check your privacy compliance arrangements. Celebrate if you are sure there is no gap anywhere.

Celebrate also if you are an individual user of healthcare services. Now you know exactly what your rights are under the HIPAA Privacy Rule!